When we consider the reasons supporting or hindering adoption of AI, there might be a tendency to focus on rational aspects, namely the trade-off between benefits such as time-savings or enhanced performance, on the one hand, and costs such as learning effort or the consequence of mistakes, on the other.

But we are also emotional beings (and not particularly rational, either). So, alongside the costs and benefits of using AI, it is also important to consider how psychological aspects may impact on use. This blog post considers three emotional factors that may be shaping AI resistance: technophobia, scepticism and speciesism.

🔌 Technophobia

One emotional barrier to AI adoption is technophobia, an intense fear or dislike of technology resulting in its avoidance. This fear can result from not understanding how the technology works, as in the case of early reactions to electricity. Alternatively, it can arise from anxiety about the impact of technology on, for instance, nature, personal safety, ways of living, or livelihoods.

Li Zhao, Qile He, Muhammad Mustafa Kamal and Nicholas O’Regan looked specifically at the impact of technophobia on adoption of generative AI (GenAI) in organisations. In their paper “Technophobia and the manager’s intention to adopt generative AI: the impact of self-regulated learning and open organisational culture“, Zhao and colleagues surveyed 528 managers in China and found that technophobia was stopping some of them from engaging with generative AI (b = -0.198).

Though, they also found that this negative effect was muffled in organisations that encourage innovation and experimentation, because in such environments “managers can easily access information about generative AI, boosting their confidence and reducing technophobia. Open communication further supports AI adoption by encouraging feedback and strategy adjustments.”

They posit that technophobia may impact on adoption of generative AI because:

- Anxiety and unease towards GenAI may lead managers to avoid the technology

- Technophobia may also lead managers to overvalue GenAI’s potential risks and undervalue its benefits

- Managers may doubt their own ability to understand and use the technology

Their data was focused on the organisational context in China and may not be relevant for other contexts for two reasons. First, workplace mistakes may have more severe consequences than mistakes done in an informal context. Second, ‘losing face’ may be a heightened concern in Confucian cultures. Still, in my view, this study suggests that researchers and managers might wish to investigate the impact of technophobia on use of AI in other contexts, too.

An open access version of the paper is available here.

🕵️♀️ Scepticism

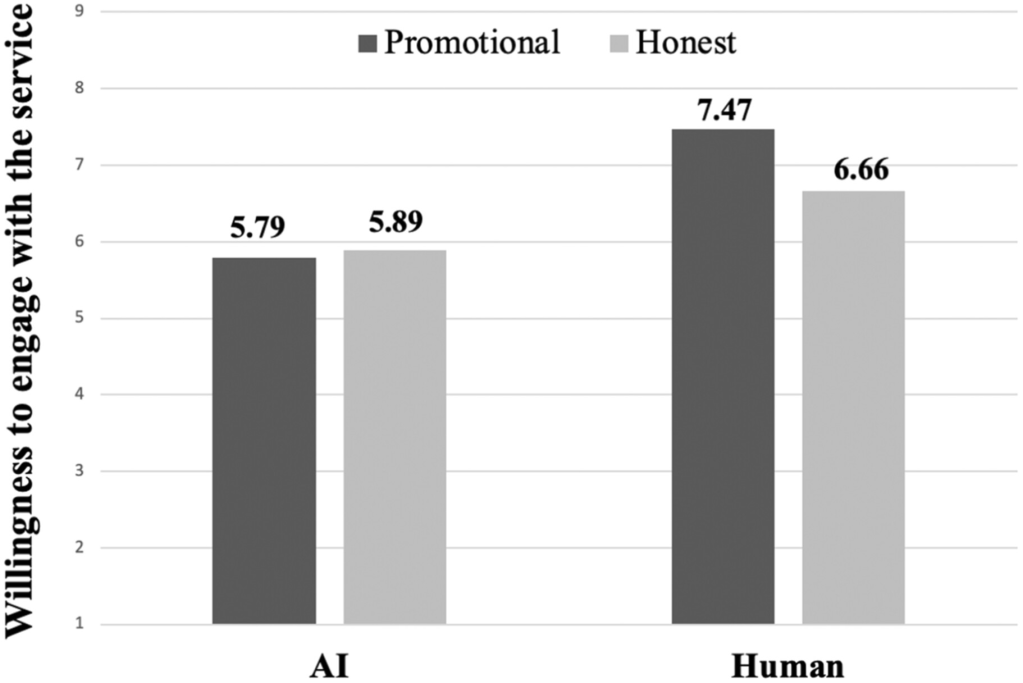

Darina Vorobeva, Diego Costa Pinto, Héctor González-Jiménez and Nuno António found, through a series of studies, that “companies’ self-promotion of AI-based resources” can have “a detrimental effect on (customers’) willingness to engage”.

Their data indicates that customers are suspicious of promotional messages that describe AI service assistants as “best”, “top” or “leading”, with some perceiving those messages as exaggerated and dishonest. Vorobeva and colleagues also find that customers tend not to trust claims about the value of AI service assistants but will trust the same claims made about human service assistants.

These results mean that businesses need to be cautious about their promotional efforts around AI, so that they are not seen as bragging and, therefore, do not lose credibility.

You can read about the work done by Vorobeva and colleagues, in the paper “Bragging About Valuable Resources? The Dual Effect of Companies’ AI and Human Self-Promotion”, published in the Psychology & Marketing journal.

🐾 Speciesism

Speciesism refers to the bias towards one’s own species, and against members of other species. When applied to humans, it translates into the belief that humans are superior to, and have more rights than, other species (animals, plants, etc…). Specieists (i.e., people who believe that humans are superior to other species) tend to disregard the well-being of non-human animals and other entities. For instance, meat eaters tend to have higher levels of speciesism than vegans, and the same for adults vs. children.

Researchers have examined how speciesism could shape service preferences, too. For instance, Schmitt (2020) predicted that specieists would prefer to interact with other humans and resist service automation, and some empirical research corroborate this idea.

However, research by Weiwei Huo, Zihan Zhang, Jingjing Qu, Jiaqi Yan, Siyuan Yan, Jinyi Yan and Bowen Shi, in a medica context, suggests that the effect of speciesism may be nuanced. Specifically, Huo and colleagues found that specieists resisted AI when it acted independently in the service interaction (e.g., made a diagnosis). However, they accepted the AI when it performed a supportive role (e.g., analysed medical exams to determine the extent of patients’ lung damage, but did not make a diagnosis).

Furthermore, Artur Modliński and Rebecca K. Trump showed that specieists’ willingness to engaged with AI also depended on the type of task. Namely, the researchers found that specieists had a favourable attitude towards the use of AI in mundane (e.g., tracking an order) or undesirable (e.g., awkward interactions) tasks.

Taken together these studies suggest that while customers high in speciesism may resist AI, in general, they may be ready use AI when it takes a subordinate role and when it is used (effectively) for mundane or undesirable tasks.

A note of caution

While these studies may offer valuable insights, it is important to acknowledge that it is harder to “spot” psychological traits such as technophobia, scepticism or speciesism, than socio-economic, demographic or geographical attributes.

Usually, psychographic traits need to be inferred from actions such as consumers’ media consumption habits, social class or lifestyle (or, in the case of business customers, from the company’s culture or power structure). But… that’s a whole other post.

The main implication from these papers, I think, is that, for the time being, we should make interactions with AI voluntary, not oversell AI’s features (e.g., AI can analyse lots of data, instead of AI knows how you feel), and frame AI’s use as supporting the customer (e.g., saving time) rather than knowing best.

As we move further into an AI-driven world, the key question is not what the technology can do but, rather, how people feel about using it.