It has been noted by many different people that large language models (LLMs) can, to a certain extent, democratise access to information. Because these models are trained on massive datasets, and use an intuitive prompt-and-response format, they enable users to quickly learn the basics on a given topic or, conversely, do a deep dive on narrow topics of interest. For instance, I have been having an exchange on ChatGPT about “getting into gardening”, which started with general information about things to consider such as light, soil, basic tools, etc… and has now progressed to specific suggestions about what to do at different times of the year, given the area where I live and, even, which local resources and garden centres to visit for inspiration and advice.

Though, a key problem with generative AI based on LLMs is that this technology produces answers by predicting the next most likely token. Thus, the stronger the correlation between the tokens in the training datasets, the more likely the response will reflect that. As the training datasets reflect human biases, the resulting answers are likely to display the same stereotypes, gaps and mistakes that populate the Internet. Thus, while LLMs can support democratisation of information for the topics and populations that are represented in the training datasets, the groups under- or misrepresented in the data will also be under- or misrepresented in the resulting answers.

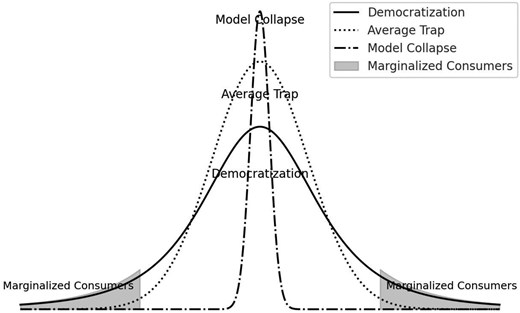

Bias is a challenge in the short term. But Ming-Hui Huang and Roland T. Rust warn that there’s an even bigger risk on the horizon. In the paper entitled “The GenAI Future of Consumer Research”, published in Journal of Consumer Research, Huang and Rust argue that “as more researchers rely on GenAI tools, these models start reinforcing dominant trends from past studies” and “conclusions begin to converging towards similar conclusions” creating what the authors call the “average trap”:

“GenAI models operate using autoregressive processes to predict the most likely next token(s). Since the average represents the most common value in a dataset, next-token prediction models naturally generate outputs that gravitate toward the average (…) The longer tail of the distribution may not meaningfully influence the generated outputs, which will continue to reflect average behaviours. This average trap leads to generic responses that miss nuances essential for marketing and consumption.”

Huang and Rust add that “when LLMs are repeatedly trained on data produced by their previous generations, (they lose) information about the tail of the distribution over generations”. As a result, “data primarily reflect machine behaviour rather than human behaviour. Consequently, next-token prediction models begin forecasting the next most likely machine action rather than genuine human preferences. In this scenario, GenAI falls into a self-reinforcing cycle—predicting and replicating its own behaviour—ultimately producing outputs that may no longer make meaningful sense to consumers”. Huang and Rust refer to this stage as model collapse.

In other words, while generative AI can democratise access to information, it does so at the risk of bias in the short term, and homogenisation in the medium term.

As a consumer of information, this means that LLMs are great for quickly learning about the mainstream views on a broad range of topics. However, they will have limited value for nuanced views and minority perspectives. Going back to my gardening example, I would need to complement the information provided with advice from my neighbours or other local experts.

In turn, when used in a professional context, LLMs risk producing answers that lack originality and reinforce “sameness”. If I was relying solely on LLMs to write a blog post about gardening, I might end up with the same ideas as everybody else, rather than something that reflected my unique experience and perspective.

To avoid falling into the ‘average trap,’ we need to balance what AI offers with other sources. Where do you turn to, when you want to move beyond the mainstream?