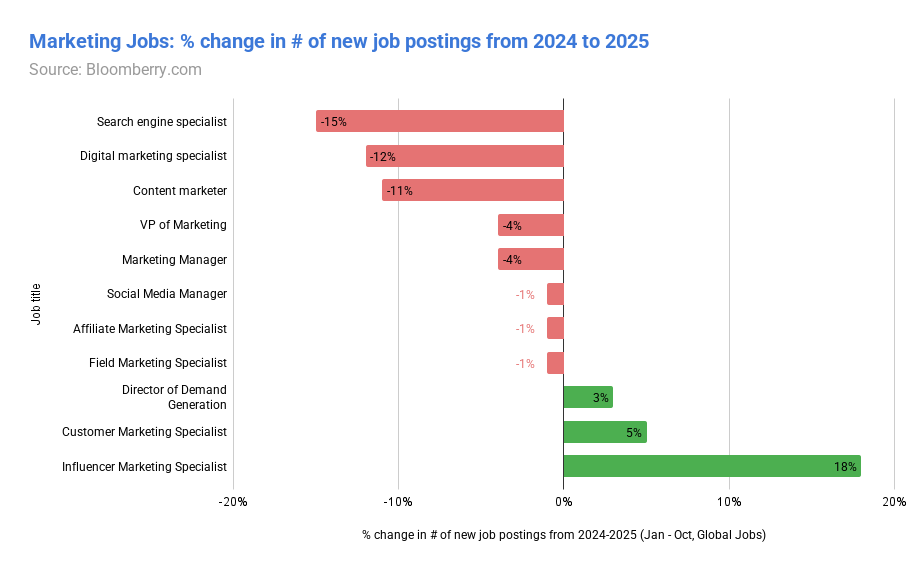

A recent analysis of nearly 180 million global job postings from 2023 to 2025, by Henley Wing Chiu at Bloomberry, reveals an interesting split in labour market trends. Execution-focused, creative jobs are experiencing steep declines. For instance, in the two years covered by this analysis, computer graphic artist roles are down by 33%, writer roles by 28%, search engine specialist roles by 15%, and content marketer roles by 11%. Likely, this trend is because these are precisely the kinds of jobs where generative AI can now produce good outputs at remarkable speed and low cost.

In contrast, influencer marketing roles have increased 18% this year, building on a 10% rise in the previous one.

Chiu explains that “as people flood the internet with AI content, traditional channels are losing what little trust they had left. Search results? Increasingly AI-generated slop. Display ads? Always annoying, now potentially AI-designed. Cold emails? Obviously AI-written and sprayed to a bunch of random strangers. People are developing an immune response to everything in the internet. But a skincare video from a TikTok creator their age? That still feels real and genuine.”

That is, the rise of AI-generated content has created a trust deficit, prompting audiences to give more weight to voices that feel authentic, relatable and rooted in real human experience.

The paper “Creating, Metavoicing, and Propagating: A Road Map for Understanding User Roles in Computational Advertising”, by Yuping Liu-Thompkins, Ewa Maslowska, Yuqing Ren and Hyejin Kim, and published in the Journal of Advertising may help understand this phenomenon. Liu-Thompkins and her co-authors argue that everyday users of a product can play three roles in its advertising.

The first role is as creator, producing content about the brand, such as product reviews. The second role is as metavoicer, reacting, commenting and remixing content about the brand. For instance, via likes, comments or up / down votes. As the authors note, these actions “add metaknowledge to the original content. Such metaknowledge can help other users, especially those who have not viewed the content, to assess the potential value of the content and whether they should engage with it” (page 6). The third one is as propagator, circulating content across networks (e.g., through sharing), and effectively serving “as an intermediate content broadcaster” (page 9).

Influencers typically perform, simultaneously, all three roles identified by Liu-Thompkins and colleagues. They create content, respond to cultural conversations, stimulate reactions, and ensure that content travels widely. Their value lies not only in the production of content, but in the relationships that they build with their audiences, and which are not easily replicated by generative models. As generative AI massively increases the volume of online content, human voices become more important because they help audiences filter noise and identify what is credible, relevant and engaging. Moreover, influencers excel at content such as use of humour, timely cultural references, or emotional resonance, which gain traction with platform algorithms over and above simple posting volume or frequency.

In my view, the bifurcation that we are seeing in the advertising job market is an indication of what may happen in other professions: Roles built around execution or routine creative output will likely shrinking as generative AI makes production quick and high-quality. Meanwhile, roles centred on trust, strategic judgement and social understanding may expand. If AI keeps accelerating, which parts of your role become more valuable — and which parts less?