You might have seen this graph, already. It depicts an explosion in the use of the term “delving into” in academic papers and is used as evidence that authors are writing academic papers with LLMs.

Similar messages are flying online, pointing to other words overused by AI such as intricate, complexity, intersection, nuanced or stakeholders.

This rush to find indicators of humans cheating with machines, reminded me of the paper “Reverse Turing Tests: Are Humans Becoming More Machine-Like?”. In this paper, Brett M. Frischmann notes that, as humans are shaped by their environment, and technology is part of that environment, then technology also shapes humans. Further, he argues that technology’s influence, particularly automation, may diminish what it is to be human. The purpose of Frischmann’s paper, thus, is to propose a methodology to allow us to check whether we are interacting with another human, in contexts where we suspect humans might have been replaced with machines.

To that end, Frischmann turns the famous Turing Test on its head.

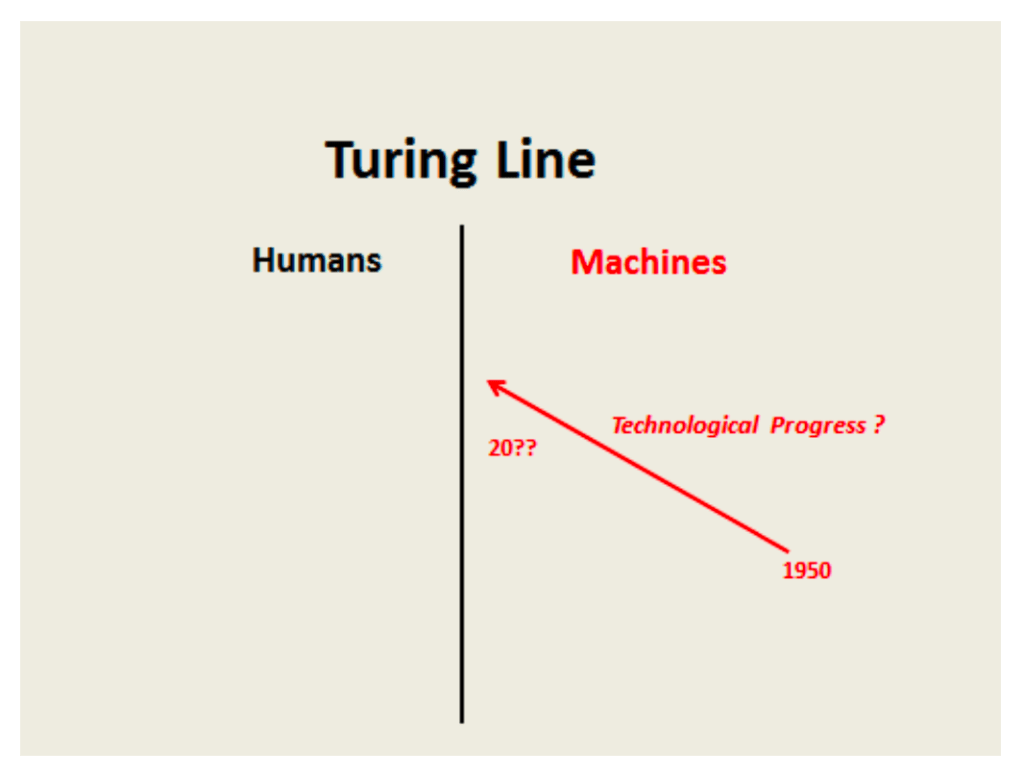

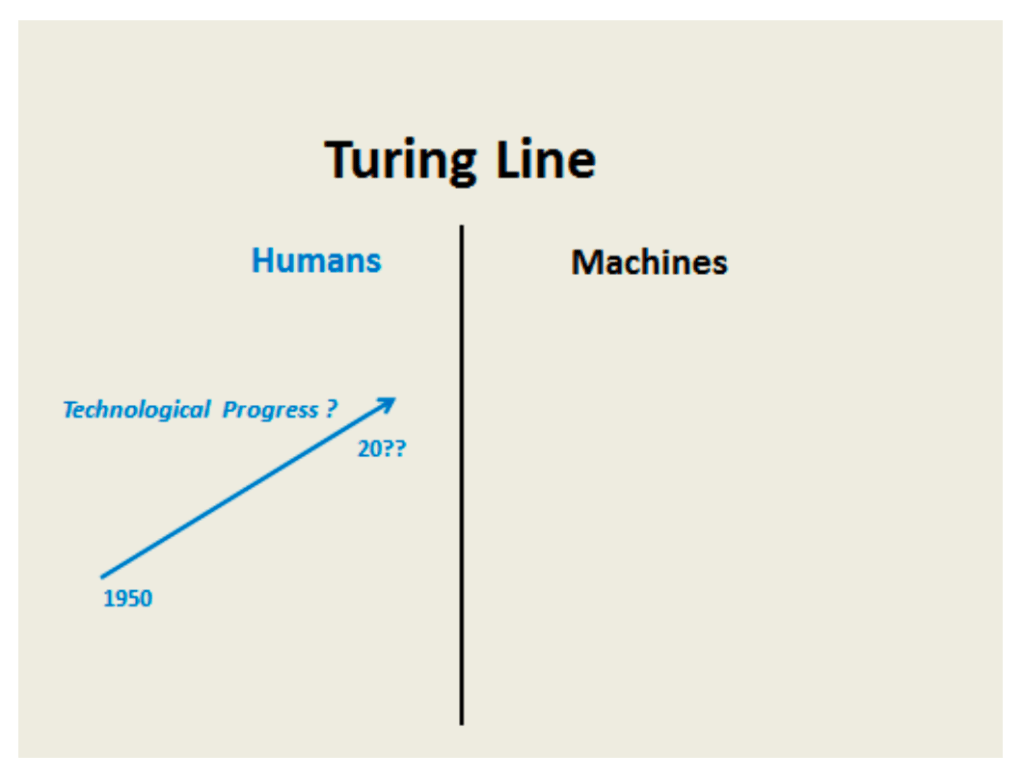

The Turing test aims to detect when a machine exhibits human-like intelligence behaviour by having an interrogator interact with an hidden party, for 5 minutes, via text. If the interrogator can’t confidently say whether the hidden partner is a human or a machine, then the machine is said to be human-like. This test, Frischmann argues, implies that there is a line separating humans from machines, and that technological progress brings technology closer and closer to that line, such that there is a point beyond which a machine is indistinguishable from a human being.

At the same time, technological progress has resulted in humans behaving more and more like machines. He uses the example of a NY Times journalist who was absolutely convinced he had been interacting with a computer, at a call centre, and was somehow disappointed when he realised his interlocutor was, indeed, a human.

Thus, Frischmann looks at the other side of the line and proposes four tests to distinguish humans from machines:

- Mathematical computation – most humans would make errors under time pressure, and would be unable to complete complex calculations;

- Random numbers’ generation – machines generate random numbers in a “predictable” way, based on the seed number and the algorithm;

- Common sense – machines can’t draw on “shared core knowledge base, language, and social interactions sufficient to generate common understandings and beliefs” (page 27) to solve everyday problems;

- Rationality – machines solve problems in a rational manner, whereas humans exhibit all sorts of cognitive biases such as “optimism bias, self-serving bias, hindsight bias” and others (p. 36)

The first test wouldn’t be relevant for non-numerical contexts, and the second one requires knowledge of the machine’s algorithm.

However, the third test would be very helpful if both the tester and the tested share the same context – for instance, the content of a module.

The usefulness of the fourth tests depends on the extent to which choices are constrained by the environment (for example, professional scripts, or nudging initiatives).

To these tests, I would add another one: creativity, or the ability to come up with original ideas. While it may be the case that our culture is converging, humans still manage to be more creative that AI, particularly if they work in groups, as discussed in this video:

What “clues” do you use, if you need to distinguish between a human and an AI?