When we don’t know that an algorithm has been used to make a decision that impacts us, we can’t challenge those decisions, or fix any mistakes. According to Anne-Britt Gran, Peter Booth and Taina Bucher, such lack of awareness constitutes a new form of digital divide:

“Not only does a lack of algorithm awareness pose a threat to democratic participation in terms of access to information, but users are performatively involved in shaping their own conditions of information access. (…) New divides are created based on the uneven distribution of data and knowledge, between those who have the means to question the processes of datafication and those who lack the necessary resources”.

Therefore, Gran, Booth, Bucher and many others have argued that there is a moral as well as a legal imperative to force institutions to be transparent about their use of algorithms. I thought that it was a great idea, too.

However, I have now come across a study that suggest that transparency about the use of algorithms in decision making can have a very negative side-effect: triggering a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The new study

Researchers Kevin Bauer and Andrej Gill examined how people behave after being informed about how an algorithm scored them. In simplified terms, their study proceeded as follows

- Participants joined a simulation and were asked to complete a survey

- Then, they were told that they had borrowed some money, and had to make a decision regarding how much to repay to the investor

- Their payout was a function of how chose their repayment was to the investor’s expectations

- In addition, some participants were told that, based on their survey responses, predictions had been made about how much they were likely to repay by an algorithm or by a human expert (see table 1).

- Then, they decide how much to repay

Table 1. Overview of scenarios

| Prediction Source | Disclosure Type | Decision-Maker Access |

| Algorithm | Public | Both User and Investor see the score |

| Algorithm | Private | Only the User sees the score |

| Human Expert | Public | Both User and Investor see the score |

| Human Expert | Private | Only the User sees the score |

| Control | None | No scores are generated or shown |

The researchers found that disclosing that an algorithm had been used to score the participants behaviour, and what the result of that prediction was, even when it was wrong, led participants to align their behaviour with the prediction, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy, such that they end up creating the world that the algorithm had (erroneously) predicted.

As the authors explain:

“Self-fulfilling prophecies seem to occur because scored individuals act less according to their fundamental (behavioural) inclinations and more as predicted by the inaccurate algorithmic scores. Because self-fulfilling prophecies endogenously alter the observed ground truth labels of data subjects, algorithmic transparency affects the accuracy of the scoring system, allowing it to create the (mis)predicted world without necessarily being noticed by human supervisors” (p 238)

Implications

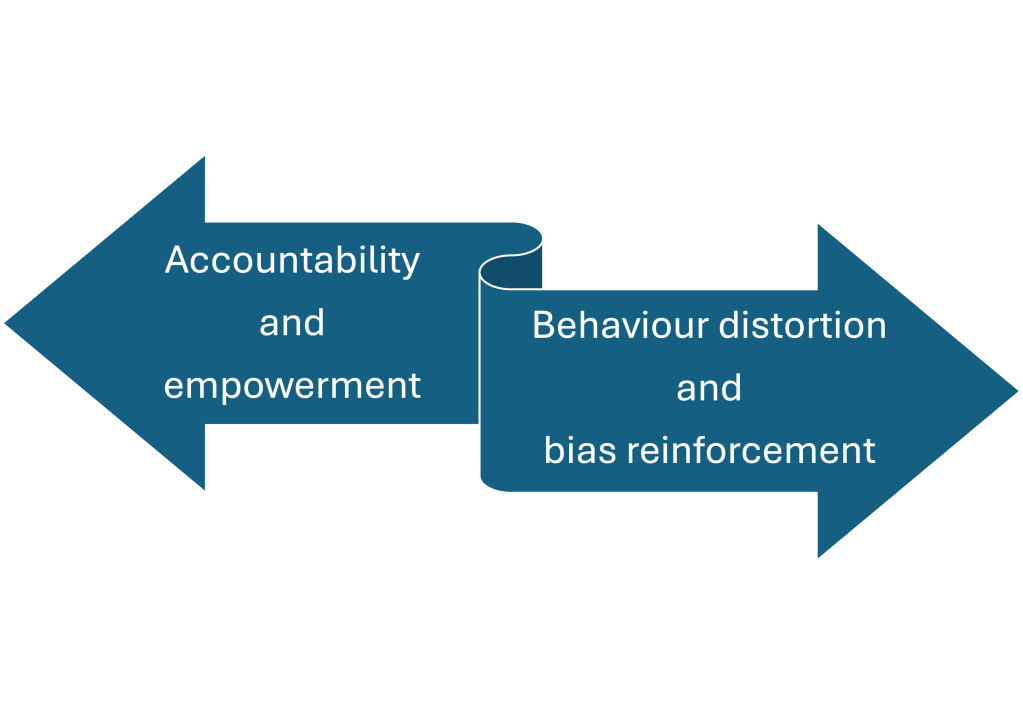

Bauer and Gill’s research reveals two critical downstream risks of algorithmic transparency.

First, a direct effect on human behaviour, because knowledge about the algorithm’s decision actively reshapes how people act, steering them toward the (mis)behaviours that the algorithm “predicted”.

Second, an indirect effect on the algorithm itself, because when managers see a person behaving as the algorithm predicted, they may mistakenly believe that the algorithm was correct in the first place. This could reinforce automation bias, leading humans to follow algorithmic assessments even more blindly than in the past.

Bauer and Gill’s research was reported in the article “Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: Algorithmic Assessments, Transparency, and Self-Fulfilling Prophecies”, which published in volume 35, issue 1 of the Journal “Information Systems Research”.

In summary, we are facing a paradox. On the one hand, we need transparency for accountability. On the other hand, transparency itself corrupts the behaviour being measured.

Given that “knowing the score” changes our behaviour, how can we design transparency that empowers us to challenge a decision without inadvertently nudging us to conform to it?