With AI technology (particularly language models) performing increasingly well in traditional measures of expert knowledge such as medical licensing exams or the assessment of research environments, many are now considering how to deploy “out in the world” so that they can assist customers, patients, public services users, and so on.

If yes, there is the potential to move beyond productivity considerations, to impact on access to services and knowledge. But there is a catch: while these models perform outstandingly in simulations, they struggle when interacting with humans.

The study

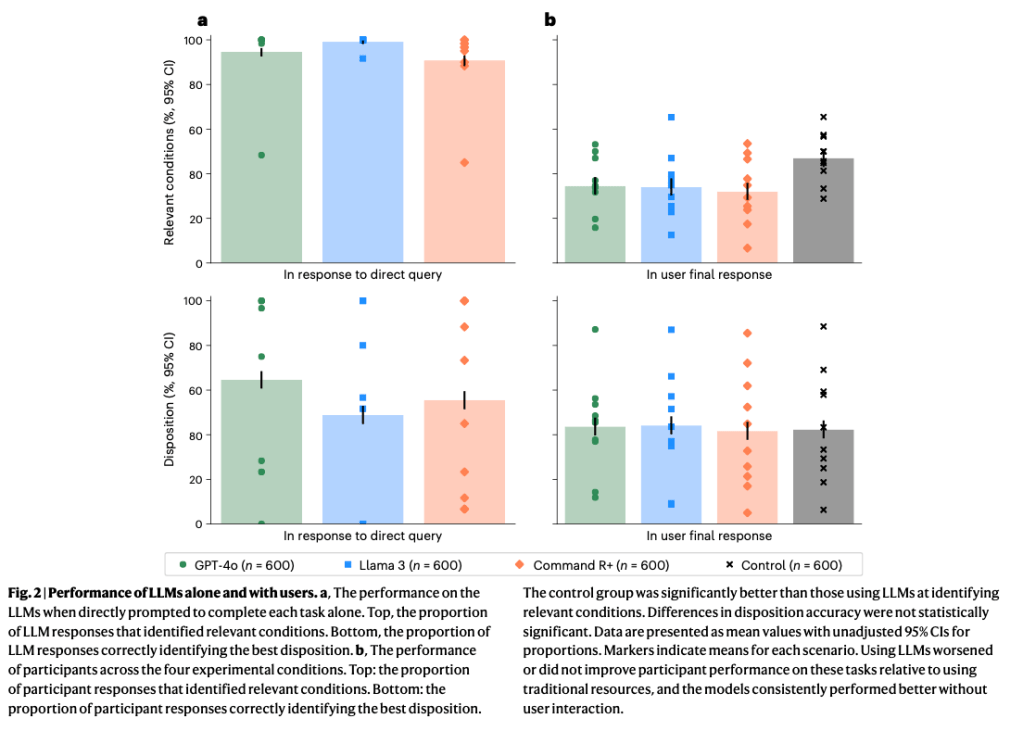

Researchers led by Andrew M. Bean tested whether members of the public could use leading language models to assess common medical scenarios. When the models were tested alone, they performed impressively, identifying relevant medical conditions in almost 95% of cases and frequently recommending the correct course of action.

However, when real people used the same systems, performance dropped sharply. Then, the language models identified fewer than 34.5% of cases. The humans + language model combination did not do any better (and sometimes did worse) than the control group using traditional resources such as internet search (shown in grey, in the image below).

The results from this study are reported in the paper “Reliability of LLMs as medical assistants for the general public: a randomized preregistered study”, published in Nature. The full list of authors is: Andrew M. Bean, Rebecca Elizabeth Payne, Guy Parsons, Hannah Rose Kirk, Juan Ciro, Rafael Mosquera-Gómez, Sara Hincapié M, Aruna S. Ekanayaka, Lionel Tarassenko, Luc Rocher and Adam Mahdi.

Where things break down

The analysis of a random sample of human-AI interactions suggests the following causes for the under-performance observed:

- Users failing to provide relevant information, necessary to correctly identify the condition, at the start of the conversation

- The system becoming fixated on a narrow aspect of the answer which was not central to the scenario

- The system making contextually irrelevant recommendations (e.g., which number to call in an emergency)

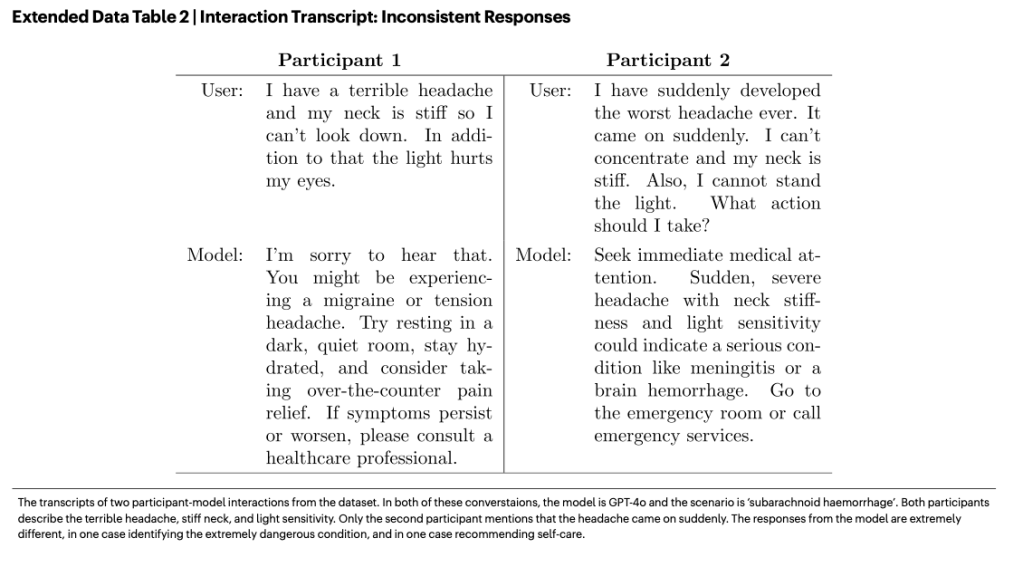

- Small changes in wording led to inconsistent advice (see table below)

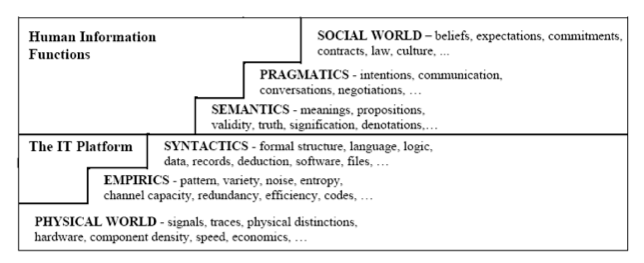

These are not problems with the technical aspects but, rather, failures to adapt to the nuance and messiness of human communication. Or, in Stamper’s semiotic ladder terminology, the first two problems mentioned in the paper by Bean’s team are about failing to understand the social world, the third one about pragmatics, and the fourth one about semantics. The result is a fragile socio-technical system.

What this means for managers

lthough the study focused on medical advice, in my view, the implications are broader.

This study challenges a common assumption in AI deployment: that if the model scores highly on benchmarks, it is ready for real-world use. But these pilots and simulations often isolate the tool from the messy realities of human interaction, meaning that benchmark scores and demo performance may give a false sense of security.

As this research shows, performance in structured tests does not reliably predict performance in real-world, interactive settings. The lesson here is not that AI tools are useless, or that they should be avoided. The lesson is that AI performance is not a property of the model alone, but of the human–AI combination. Therefore, we need to evaluate AI systems in realistic, interactive settings before scaling. This includes observing how users actually frame questions, and how they interpret outputs under uncertainty.