Since the early days of Open AI’s release of ChatGPT 3.5, many voices have alerted to the fact that, while generative AI tools produce very convincing answers, they are also prone to making up information. This propensity is referred to as hallucination.

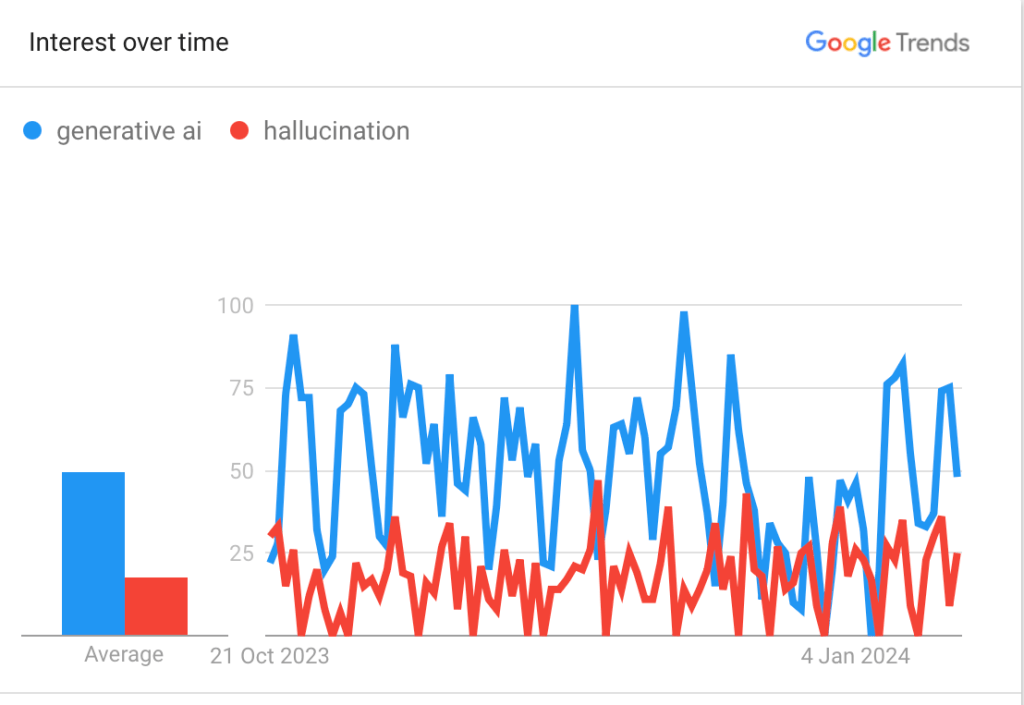

Concerns over generative AI’s propensity for hallucination are almost as prevalent as enthusiasm for its potential (see Google Trends graph, below), which shows the importance of developing guidelines on using these tools in a responsible manner. That’s why I was delighted to read Ian McCarthy’s paper “Beware of Botshit: How to Manage the Epistemic Risks of Generative Chatbots”, co-authored with Timothy R. Hannigan and André Spicer.

In this paper, Hannigan, McCarthy and Spicer focus specifically on large language models (LLMs) whose “capacity to efficiently produce content that could be hallucinatory means chatbot users and their organizations face significant epistemic risks when using this technology for work” (page 10). [i.e., significant risk related to the process of producing of knowledge].

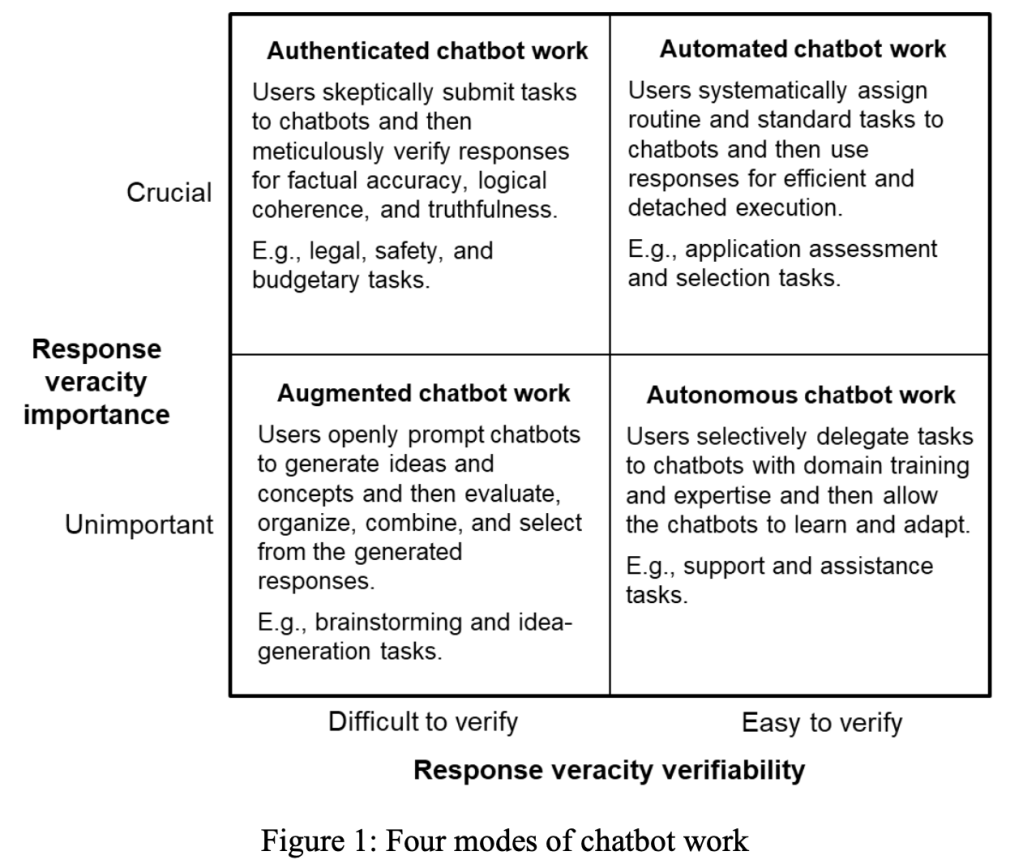

Hannigan and team propose that, to address this risk, we need to reflect on two aspects. They are:

- LLM’s response veracity verifiability – i.e., the extent to which the user can easily verify the chatbot’s response. It can range from easy to difficult.

- LLM’s response veracity importance – i.e., the extent to which the consequences of using hallucinated information are severe. It can range from unimportant to crucial.

From there, the authors propose four modes of chatbot work:

If it is crucial to get a true / correct answer and it is clear whether the answer is right or wrong, we can automate the use of LLMs to increase the efficiency of specific tasks. An example would be asking the LLM to summarise a paper that you read, already, and thus, where you can easily see whether the summary produced is correct or not.

If it is crucial to get a true / correct answer but it is not immediately clear whether the answer is correct or not, then we need to authenticate the work produced by the LLMs, by carefully checking whether the answer is correct. An example would be asking the LLM to suggest menu items for a meal where there will be guests with severe food allergies. You really want to check the list of ingredients against a trusted source, before getting started on that meal preparation!

If mistakes are acceptable and there isn’t a clear right or wrong answer, we should augment the LLMs’ answers with our own criteria for selecting the right answer. An example would be asking the LLM to suggest titles or closing questions for our blog posts, thus using the generative AI tool as a source of inspiration.

If mistakes are acceptable and it is clear whether the answer is right or wrong, then we can allow the LLMs to work autonomously. An example would be asking the LLM to create characters or scenarios that exemplify a concept that you are teaching, for use in class discussions (where the benefit is exactly in discussing if / when the answer is correct or not).

In my view this framework has a few limitations.

First, we may wrongly assess the importance of veracity. For instance, I may underestimate the importance of checking for allergens, or overestimate the importance of developing scenarios for class discussion with specific features. It is crucial that we have a good understanding of the consequences of using false information.

Second, we may wrongly assess the quality of the content produced by the LLM. For instance, I may not realise that ChatGPT 3.5 makes up references, or fail to realise that ChatGPT 4 has been trained on a lot more data than 3.5 and, thus, is many times more likely to be correct than its previous release. Or, linked to this, I may over or underestimate my ability to check whether the answer is right or wrong. Or the answer may be correct in some contexts but not others (e.g., whether it is rude to greet someone with a kiss).

Third, because the framework uses a binary classification, it over-simplifies the type of problems that we are likely to encounter. We may have applications where the importance of veracity is neither crucial nor unimportant, but rather something in between; or where the ability to verify the results is moderate. And even within a given task (e.g., summarising a paper), there may be some aspects that are important or easy to verify, and others that aren’t.

But, despite these limitations, I think that this is one of those research contributions that seems obvious once it is spelled out; but which are valuable exactly because someone made the effort of spelling it out. I really like this classification, and I am going to use it in my teaching and assessment.

Do you see any other potential flaws or limitations in the proposed framework?

4 thoughts on “A framework to decide whether and how to use generative AI chatbots”