Let me give a big shout out to the project ‘Why We Post’, which explores the nuances in social media behaviour across the world, and what that reveals about the social media users’ context and values. The website for the project contains a number of fantastic resources, including downloadable books.

While working on my sharenting project (where I explore what parents post about their children, on social media, and how those postings shape the children’s digital identities), I revisited the Why We Post website, paying particular attention to the book Visualising Facebook, co-authored by Professor Daniel Miller and Dr. Jolynna Sinanan, which you can buy or download here.

Miller and Sinanan’s analysis of Facebook posts by mothers in parts of England and Trinidad reveals that the content of these women’s Facebook posts varies significantly between the two countries.

In England, there is a clear difference in the content posted women before and after they become mothers. Pregnancies are announced on Facebook; women post photos of their growing bumps; and, after the baby is born, s/he takes centre stage in the women’s feed (e.g., by themselves, or cuddled with the mother). Often, the baby is featured in the women’s Facebook profile photo; and, sometimes, the baby even replaces the mother.

Here is an extract from the book:

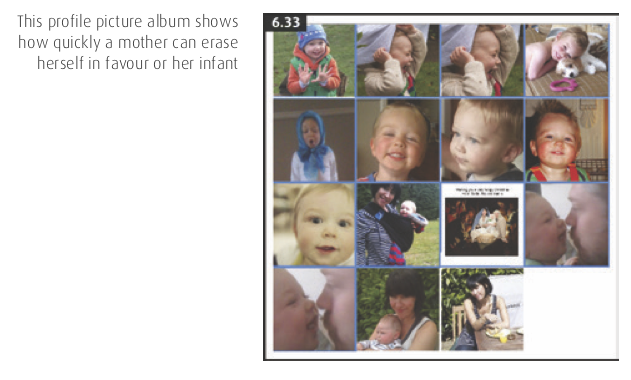

(I)t is almost always the case that if you look at the profile picture album of a mother from (England) then the pictures will be a sequence largely of that person – until she gives birth. After the birth and often for a year or two after that point, her profile pictures are more likely to be those of her infant than herself. In some instances, she virtually disappears from her own profile pictures.

This illustration is of the entire profile pictures album of one such mother. It starts with an image of her (the oldest images are at the bottom right). After the birth of her child one or two images appear that include both the infant and a parent. After a while she completely disappears, however, to be replaced entirely by the sequential images of the infant alone (Fig. 6.33). (Pp. 135-6).

Miller and Sinanan also observe that the lives of women change drastically after becoming mothers. Some take time off work, and most make new friends, for instance, by joining an ante-natal class or post-natal toddler group.

In contrast, in Trinidad, there is more a sense of continuity, both in the women’s lives and in what they post before and after the baby is born. Here is another extract from the book:

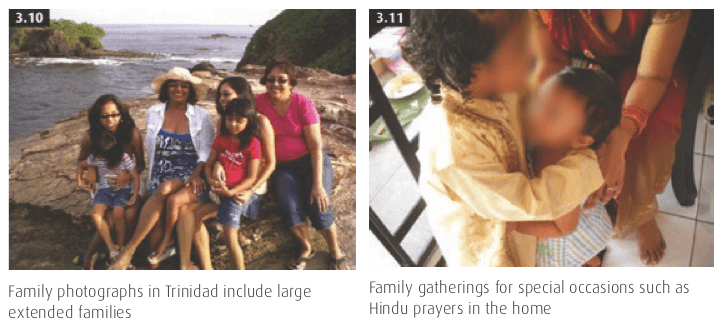

(M)others continuing to show themselves as attractive based on the cultivation of individual style. Rather than being seen ‘only’ as mothers, they still dress and pose much in the same way as they did prior to motherhood (p. 53)

Pictures of the baby by him or herself are half as common in Trinidad as they are in England. Usually, the baby is shown as part of the extended family.

For me, Miller and Sinanan’s work is really interesting on two fronts. First, it shows how, in general, motherhood assumes a very different nature in the two countries. In England, it is a transition point in the woman’s life, with new friends and, even, a new identity. For a while, at least, the woman becomes intrinsically connected with, or even over ruled, by her identity as a mother. In Trinidad, motherhood doesn’t represent such a change in the woman’s social circle or identity. The child is absorbed into the larger family, and mothers continue to affirm their individual style, and to pursue relatively the same interests and activities. This insight is extremely valuable, for instance, in developing advertising campaigns for mothers in these two countries. In the former, you would make a very clear reference to her new role, and you would want to identify the new circle of friends; in the latter, you would focus on the woman as an individual.

Second, this example shows the importance of understanding context when studying user generated content on social media. If we were to analyse these women’s photos out of context, for instance for sentiment analysis, we might assume that a large group of them did not have children, or that they did not care about their offspring; and that would be wrong. The different Facebook content is not about the women, but rather about the context in which they are. The dominant norms in their social groups, and the behaviours of the other social media users (i.e., their likes and comments) are incentivising these two groups of women to share very different types of content.

Did I say that this study was interesting on two fronts? Make it three. This study also shows the value of qualitative research in consumer behaviour – because not everything that counts can be counted.